Introduction

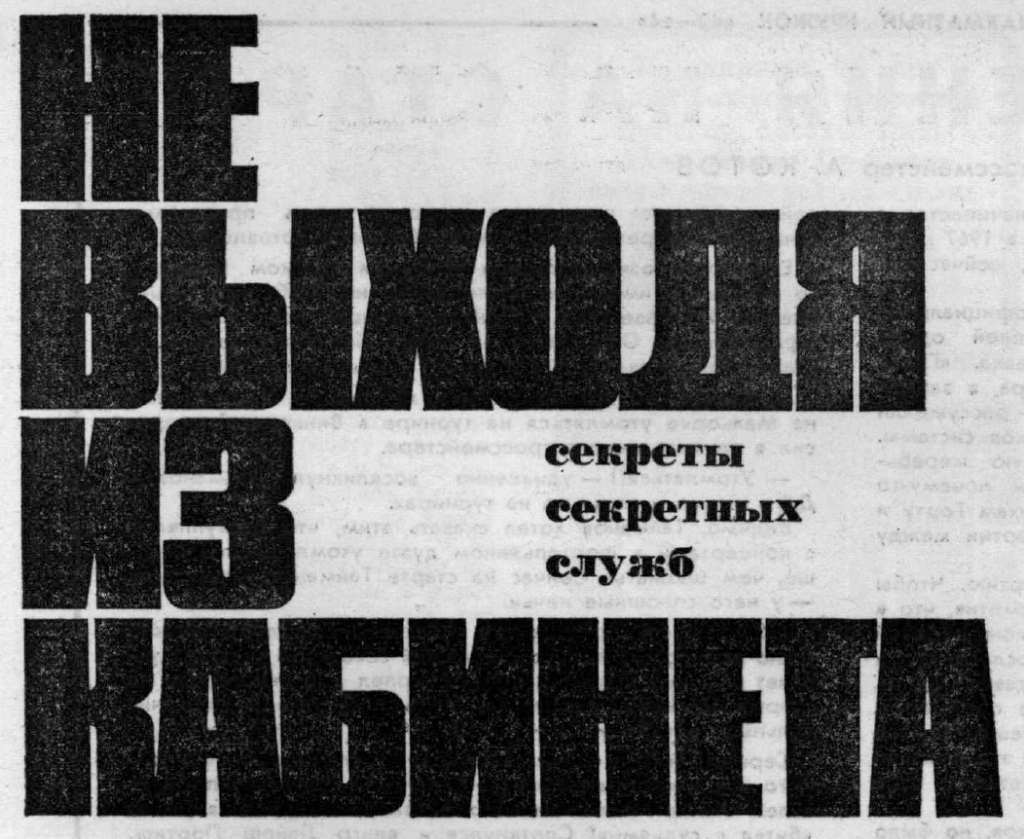

Sometimes during research, you come across a single document that, in itself, justifies the entire endeavour. This happened some weeks ago, when I stumbled upon an article from 1970, originally published in Nedelya, a popular Soviet weekly at the time. Written by “F. Sergeyev”, almost certainly a pseudonym, the article with the title ‘Without leaving the office’ (original: Не выходя из кабинета) describes the use of information from open sources by the intelligence services of “imperialist countries”, with which obviously primarily the United States are meant.

The article provides a remarkably detailed account of the Soviet perspective on US open-source intelligence practices and, in effect, also offers some insight into Soviet Intelligence information operations. As those insights are rare, I will dive into the content and relevance of this article.

OSINT during the Cold War

Not much detail has been surfaced on the extent to, and methods by which Soviet Intelligence exploited open sources during the Cold War to support its understanding of the world. By contrast, practices within the US intelligence community for exploiting open sources for intelligence purposes have been thoroughly documented, both in open publications and in material later declassified (see, for example, Bagnall 1958; Moore 1963).

Declassified articles from Studies in Intelligence show that the CIA understood the Soviets to maintain a collection programme for academic literature (see, for example, Becker 1957), although those efforts appear to have focused on acquiring technical knowledge (e.g. CIA 1985) rather than information for use in intelligence estimates. Whether the KGB systematically collected and analysed open-source materials for intelligence purposes at all is therefore uncertain. Andrew and Mitrokhin devote only a single reference to the use of open-source material (1999: 304).

Richelson (1986) however dedicates a 25-page chapter to the use of open sources in his book on the Soviet Intelligence and security apparatus. While he suggests that open sources were widely used by the Soviets, closer scrutiny of his sources reveals only limited evidence for this claim, if at all. Only one small paragraph referenced from a Soviet source (Sokolovskii’s ‘Soviet Military Strategy’ 1975, page 320) appears to support his argument:

However, upon closer scrutiny of Sokolovskii’s work, this paragraph does not refer to activities of Soviet Intelligence in the section where the quote is taken from, though clearly to the intelligence services of the ‘imperialist countries’. Richelson’s use of the quote thus appears incorrect. And the rest of the chapter details what could be possible, rather than detailing actual Soviet practices and no further sources are referenced by him.

Orlov (1963) provides another perspective. In his account, Soviet services obtained information from two principal sources: secret informants and undercover agents on the one hand, and legitimate sources such as military and scientific journals, reference works, and parliamentary records on the other. However, according to him, Soviet Intelligence regards as true intelligence (razvedka) only the first type, procured by covert means in defiance of foreign law, while information from open sources was treated merely as research data. In other words, covert collection lay at the core of Soviet Intelligence doctrine, and overt methods were not even classified as “intelligence”.

This perspective can also be observed in an old KGB manual on ‘Information work’ which was made public some years ago. In the manual, as the first requirement for ‘intelligence information’, it is prescribed that the information should be truly secret, covering the behind-the-scenes side of events, secret plans and intentions of the enemy (KGB, undated. See also a previous post on this manual). It is explicitly mentioned that no value is seen in information from open sources.

There are also some accounts on the collection and exploitation of open sources by Soviet intelligence in the preparation and support of ‘active measures’, see for example Serscikov (2024) who references a KGB assessment of Lithuanian émigré publications (Kontrimas 1986). However, examples of structured collection and exploitation of information from open sources by Soviet Intelligence to support intelligence assessments, so far seem non-existing. The 1970 article, however, casts the issue in a different light, as will be explained below.

The 1970 article

The 10,000-word article appeared in two parts in issues 46 and 47 of Nedelya in 1970 and opens with the proposition that:

‘today’s intelligence agency is primarily a vast scientific research establishment, relying not so much on secret, conspiratorial methods as on modern capabilities for the collection, analysis, and systematisation of data, most of which comes not from secret agents but from “overt” sources that are, in principle, accessible to anyone‘.

The article then outlines several historical cases in which military secrets were uncovered using open sources. One case discussed was Sherman Kent’s unofficial project involving five Yale scholars who reconstructed the US order of battle using only publicly available information, later known as the Yale Report (see also Winks, p. 461).

On the basis of what Sergeyev calls an analysis of American literature on the subject, he then distinguishes three basic categories in the exploitation of open sources. The first is the collection of general political, economic, and military information needed to assess the military-economic and morale-political potential of an opponent. Such data, he argues, reveal the fundamental strategic orientation of the government agencies of interest.

The second category is “special intelligence information” related to specific economic and military topics. As a rule, this information is intended for a narrower circle of specialists and serves as input for the development of strategic plans. The third category, where open sources play a particularly significant role, is the collection of information about individuals, not only statesmen and politicians, but also members of the younger generation.

Sergeyev concludes that, while open sources may not contain classified information, painstaking and systematic study of the entire body of published material, combined with analysis, synthesis, and evaluation, can provide an intelligence specialist with a fairly accurate picture of the state and trajectory of a particular field of science or economics. In other words, his opinion appears to deviate from the Soviet Intelligence practice, that as we understand so far, typically did not attach any value in information obtained from open sources.

Reflection

The two-part article is a rare example of a public Soviet discussion of intelligence collection methods during the Cold War. As such it offers valuable insight into how Soviet analysts understood Western open-source intelligence directed against their own country. In particular, the author’s aside that ‘as we can judge from American publications’ strongly suggests that he not only had access to these materials but also exploited them in a systematic way.

The article further cites statistics from Soyuzpechat, noting that in 1968 the US Embassy subscribed to 900 Soviet newspaper and magazine titles, six times more than in 1960. In addition, it reports that the Embassy held subscriptions to 130 newspaper and magazine titles from other socialist countries. The inclusion of these statistics strongly suggests that the author was most likely a KGB officer, since it is implausible that an average Soviet citizen would have access to such statistics, let alone in combination with the foreign information drawn upon in the article.

Ironically, the article was picked up and translated by the Foreign Technology Division of the US Air Force, which at the time was at the forefront of machine translation, as Sergeyev himself notes in the text. With the translation of his article, the circle was effectively complete.

No citations of Sergeyev’s original article have been identified so far. It was later republished as a chapter in Vasiliyev et al. (1973, pp. 175–198), where Sergeyev is listed as one of the authors. That chapter is cited in Olcott (2012, p. 47), but the original 1970 article itself appears to have largely escaped attention.

Conclusion

In sum, the 1970 article sheds new light on the prevailing view that Soviet Intelligence exploited open sources primarily to acquire technological know-how and, to a lesser extent, to support active measures. While it does not definitively resolve whether such information was methodically collected and exploited to support intelligence analysis and decision-making, it demonstrates that the Soviets both understood the potential value of open sources and possessed the capabilities to collect and exploit these. Future research should aim to identify their actual operational practices.

Notes

Andrew, C. & V. Mitrokhin (1999) The Mitrokhin Archive: The KGB in Europe and the West. Allen Lane.

Becker, J. (1957) ‘Comparative Survey of Soviet and US Access to Published Information’, Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 1.

CIA (1985) Soviet Acquisition of Military Significant Western technology: An Update. Approved for reseals 23-01-2014, CIA-RDP96B01172R000700060001-8.

KGB (undated) Informatsionnaya rabota v razvedke. Available at: https://www.4freerussia.org/kgbmanuals/2022/18-WorkingWithInformation.pdf

Kontrimas, V. (1986) Об акции “ИМПУЛЬС”. Internal KGB document, 30 July 1986, available at https://www.kgbveikla.lt/docs/show/2454/from:538

Moore, D. (1963) “Open Sources on Soviet Military Affairs”, Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 7.

Olcott, A. (2012) Open Source Intelligence in a Networked World. Continuum International Publishing Group.

Orlov, A. (1963) ‘The Theory and Practice of Soviet Intelligence’, in Studies in Intelligence.

Richelson, J.T. (1986) Sword and Shield: Soviet Intelligence and Security Apparatus. Ballinger Pub Co.

Sergeyev, F. (1970) Ne vikhodya iz kabineta. Nedelya, issue 46 (p.14-15), and issue 47 (p.17-23)

Serscikov, G. (2024) ‘Grey literature in the intelligence domain: twilight or revival?’, in Intelligence and National Security, 39:6, 1028-1050

Sokolovskii, V.D. (1975) Soviet Military Strategy. English language translation, third edition, Stanford Research Institute.

Vasiliyev, V.N. et al. (1973) Sekrety Sekretnykh Sluzhb SShA. Moscow: Izd. Politcheskoy Literatury.

Winks, R.W. (1989) Cloak & Gown. Scholars in the Secret War, 1939-1961. New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc.